On archiving memories that don't exist

Why I'm obsessed with taking pictures

A couple of days ago I tried drawing my family tree from memory. I’m ashamed to say that I could only go as far as my grandparents.

A fledgling, barren tree.

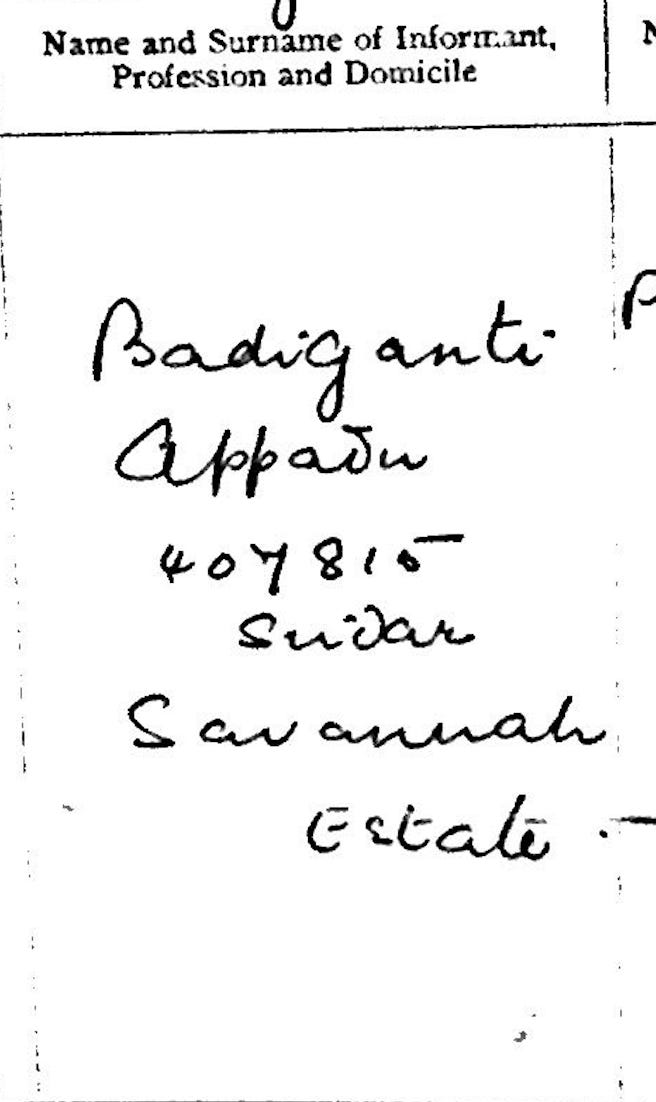

It’s hard to feel rooted when access to archives in Mauritius is limited. My family is part of the unlucky ones with no pictures associated to the indentured numbers that were used to identify workers sent from India to Mauritius on ships in the 19th century. We’re not even sure if our surname is our actual surname or the one British colonisers decided to write down as our ancestors went past their stations.

I am at the tip of a lonely branch that has no memory, no deep roots.

I started reading Laurent Mauviginier’s La Maison Vide and in the first chapters he sets the scene by tracing his great grandparents’ and ancestors’ lives. He has access to medals, diary entries, photographs, physical relics that set in stone the existence of his bloodline across centuries. Access to tombstones, to marriage registries, livrets de famille, birth certificates - official paraphernalia that confirms one’s passage on Earth, a privilege that isn’t awarded to those of us whose existence is directly tied to forced colonial displacement. There isn’t much to hold onto as we try to dig into our past. More often than not, we peer into a gaping, dark hole, squinting for a sign, a proof of life.

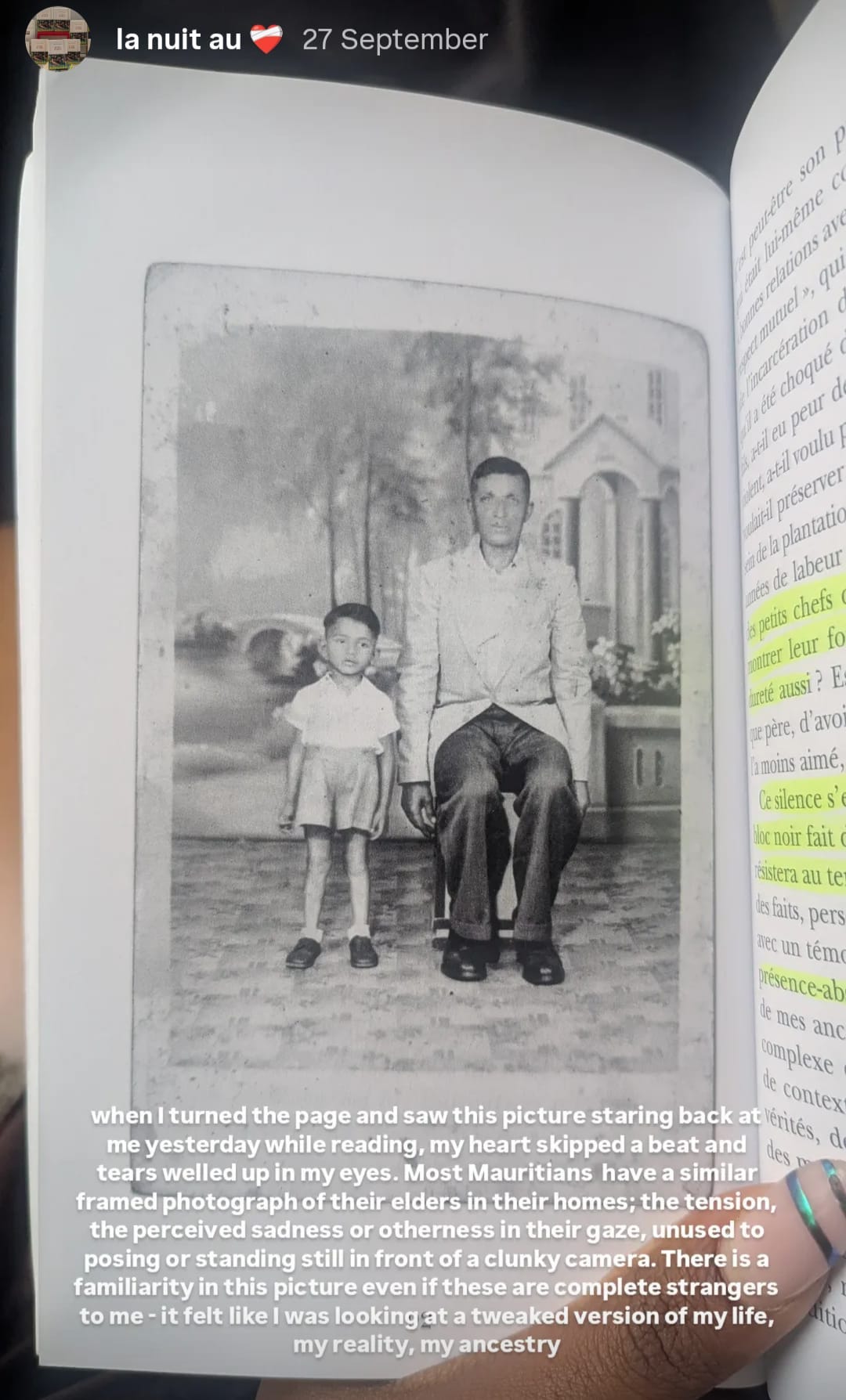

In my family, like many Mauritian families, we have this obsession with taking pictures. Immortalising moments. We have thick photo albums at home, nestled under the living room coffee tables, or stuffed into the creaky drawers of heavy, mahogany cupboards like the one’s at my Mam’s house. As a pre-Internet child I would spend hours pouring over old pictures, flipping through the images of familiar and unfamiliar faces of my parents’ and my grandparents’ generations. It felt bizarre to see my parents as young adults, teenagers, and children, peering at me through their sepia form, adorned in thick moustaches and big permed hair.

It also felt important. Weddings, birthdays, cousin outings, funerals - every Kodak envelope is stuffed with milestones and memories. Some of them contain spools of black film that were never developed.

I always badger my grandmother and my aunt with questions whenever I come across unfamiliar faces. “Kisan-la sa?” They would furrow their brows, taking a closer look at the pictures. My grandmother has had several health issues over the years and her short-term memory took a hit, but she remembers a lot from her past. I get detailed background checks on random people who used to swing by the house, of relatives who brought ill-will to the family, like the brothers of my great-grandfather who apparently sold the land that was given to the family from the Savannah sugar estate to pay off their gambling debts. I would be leading a very different life right now if they had held onto the land (but I’d probably turn out to be an insufferable privileged Indo-Mauritian so maybe it’s not so bad that they lost everything after all).

I wonder if our obsession with taking pictures is linked to the absence of physical memories beyond those of our great-grandparents who arrived in Mauritius pretty much as blank slates. Nathacha Appanah refers to it a “présence-absence” in her book La mémoire délavée, in which she traces her great-great grandparents’ history on a sugar estate in Mauritius. I wonder if my great-grandfather Badiganti Appadu spoke in Telegu to his son, my grandfather. I wonder how much of Badiganti’s life was lost in translation to his son, if there was even an attempt to pass on anything from his life in India.

Every year that goes by quickens the disappearance of my grandmother’s generation, and with them stories and links to our past that were never passed on to us. I’ve had bouts of insomnia thinking of all that we’ve lost, unable to properly take stock of the degree of loss, the degree of absence, because I can’t measure what I don’t know.

As I work my way through the pictures, I think of the past but also of the future; what photographic evidence and footprint are we setting aside for the next generations? As we’ve switched to phone-based cameras and digital photography, most of our memories are stored in the cloud, virtual bytes of memory that could be wiped out or completely transformed by AI. There was a TikTok trend this year where parents shared Snapchat filtered pictures of their children born in 2016. Some parents admitted that they didn’t have any other memories but those dog-filter or crown filter photos of their children. Obviously “not-all-parents” but I find it fascinating, and slightly devastating, that the way we capture moments today is so wildly different than how it used to be in the 1990s.

I feel like we’ve lost the solemnity of old pictures, where every roll of film mattered so hard that we had to practice our deep stare into the abyss of the lens and try not to blink. If my generation lacks photographic evidence from the past, will future generations even be able to trust the photos we pass on to them, now that AI can pretty much replicate human faces and poses?

In the meantime, I will keep taking pictures of both the mundane and the extraordinary, continue printing photos because I don’t trust any cloud providers with my data (and I don’t want AI models to train on my personal pictures, although it’s probably already doing it as we speak).

In the meantime I will always visit art exhibitions about photographic memory, like Tyler Mitchell’s spectacular Wish This Was Real, a contemporary exhibition that surprisingly feels ancient and archival. I also randomly stumbled across the “Ne m’oublie pas” by Jean-Marie Donat exhibition yesterday while ranking up my 20k steps in Paris. It’s a dense piece of work that traces the official portraits of immigrant families from Algeria, Comoros, Armenia, and other countries, taken by the Studio Rex in Marseille in the 1960s-80s. Their solemn poses in Western attire felt eerily familiar. I am also grateful for the work of artists like Audrey Albert, a Chagossian-Mauritian photographer who works on imagining and archiving the lives of Chagossians before they were forcibly displaced and uprooted from their islands.

These works of art and memory give me hope. I will make the most of every trip back home to keep badgering my grandmother about the past she remembers. Even if we lack physical proof, I must trust that most of our history is one that lives on within us, through oral history - and sometimes by reading between the lines of what has been left unsaid.

Beautiful and sad and relatable. I'm estranged from a big chunk of my family but still wonder about the generations that preceded me. Who were they, what were their stories, what did they survive? Presence-absence indeed.

Beautiful piece! I loved reading this. I love the analysis of looking into the past and connecting this to the now - your points on AI and pictures made me think. Also, very much relate to this piece since I went digging myself in the Mauritian archives this summer. It is not an easy process!